professor in the Department of Music. "When Nono

wrote it, a book had recently been published

with the last letters home of victims of

Fascism, and Nono set fragments of these

letters to music. I am fascinated by the

idea that, in writing this piece, Nono

was putting a progressive political

message in the foreground."

was just beginning to wane by the time

this piece was written -- but he was also a

lifelong Communist. Born in Venice, he

came of age during World War II but, despising

Mussolini, managed to avoid military service.

A lawyer by training, he turned full-time to music,

giving aesthetic expression to his political sympathies.

Schoenberg, whose modernist work -- using a novel 12-tone

technique -- was condemned by the Nazis. In 1955, Nono mar-

ried Schoenberg's daughter Nuria; the couple had two daughters.

Durazzi has been there, talked to her and done extensive

research; he has also pored over the letters and writings of

Nono, which have recently been published. What has emerged

from all of this is the portrait of a man who was passionately

committed to two things.

against the Germans," says Durazzi. "He also was fiercely loyal

to the legacy of composers of the previous generation whose

music he believed in."

started talking about having to find one's own way. His musical

style changed, too: Now it became very quiet and contemplative,

with a great deal of silence and open space."

Nono and his work is growing, particularly in England and the

United States, where he was long overlooked. Last year, a London

festival featured his work, and recently Durazzi attended a

conference devoted entirely to Nono's music.

upper-level course in 20th-century music; last fall, he taught a

graduate course related to his current research. But his research

on Nono allows him to explore both the life and music of a man

who wrote in the context of an important political struggle.

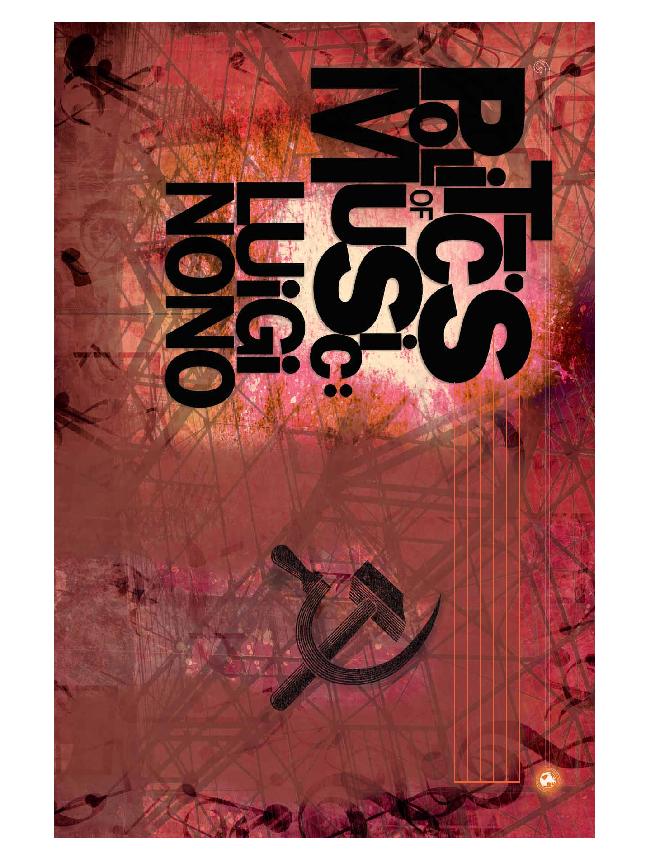

subjects that are complex,

obscure or challenging?

For example, why did

music theorist Bruce

Durazzi make Luigi Nono,

a 20th-century Italian

avant-garde composer, the

subject of his dissertation

and forthcoming book?

Nono's work is dissonant,

with clashing sounds;

for some people it is

written for chorus and orchestra. He begins his process of

composition with a simple melody, and then ruptures it,

shattering the continuity and increasing the music's complexity.

The voices fracture, too, into free-floating syllables.