a law offering compensation to the owners

of that property; if they accepted, the

squatters would take ownership of those

parcels. A number of owners agreed, but

others did not, so only some of the squatters

received title to their land.

land and those who did not? wondered

Sebastián Galiani, professor of economics.

A specialist in development economics,

particularly dedicated to the evaluation of

public policies adopted by developing

countries, Galiani launched a long-term

study of the two squatter groups.

human capital of their children," says

Galiani, who has worked as a consultant

for the World Bank, the Inter-American

Development Bank, the United Nations

and governments of South and Central

American countries, among others. "They

had smaller family sizes and their children

had a much higher secondary school

completion rate. So land titling can be an

important tool for poverty reduction."

career with international implications.

He received bachelor's and master's degrees

from universities in Argentina, his native

country, then earned a Ph.D. in economics

from Oxford University. After graduation,

he returned to Argentina to join the faculties

of the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

and Universidad de San Andrés, though

he left to take visiting professorships at

several American universities, including

Washington University.

building up its faculty and course offerings,

particularly in applied development. For

a long time, Galiani's own work had been

influenced by the work of Nobel laureate

Douglass North, Spencer T. Olin Professor

in Arts & Sciences, on the role that institu-

tions play in economic development.

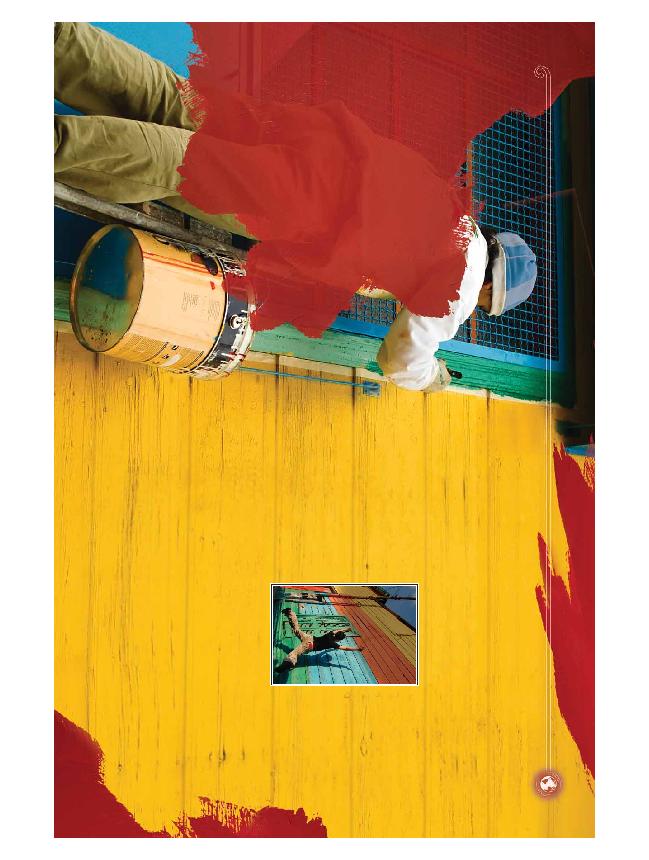

improving housing conditions for the

poor. In one recently released study, he

looked at the results of a housing

improvement program in Mexico that

replaced dirt floors with cement flooring

in the homes of some poor people.

markets; one had taken part in the

flooring program five years earlier, while

the other two had not. Working closely

with the National Institute of Health in

Mexico, he collected data on the children

in these households and interviewed

family members. Then he analyzed the

American Economic Journal and titled,

"Housing, Health, and Happiness." In the

houses with cement flooring, the children

had fewer parasites, less diarrhea or anemia

and improved overall health. The houses

were much cleaner. And mothers, too,

were happier, reporting much less stress.

involves three Latin American countries --

El Salvador, Uruguay and Peru -- in which

a Christian organization has built homes

for the poor. But do these modest homes,

located in shantytowns, improve people's

lives in the long run? Or do they encourage

people to stay in the same area, mired in

poverty, when they might otherwise have left?

government program that gives away

grocery money to the poor. The shoppers

are limited to certain stores -- which

quickly raise their prices, knowing they

have a captive clientele. Will adding new

stores to the mix improve the pricing

problem -- or will these new stores also

victimize the needy?

for his advice. He and research colleagues

also conduct courses at universities around

the world. Altogether, his work is very

satisfying, he says, both intellectually and

personally.

need answers," he says. "I hope my work

may help governments and poor countries

to adopt better policies."